On anger, misunderstandings, and hearing with different ears

Anger

Anger is a feeling that is mostly taboo in our society. People tend to think that anger and rage are the same thing and reject anger. We are taught to suppress it. But: “The suppression of anger can cause a lot of trouble, giving rise to virulent progeny such as malice, passive aggression, hostility, rage, sabotage, hate, blame, guilt, controlling behavior, shame, self-blame, and self-destruction.” (Quoted from: Anne Katherine, “Where to draw the line”).

When we talk about anger, we need to distinguish between acting out anger, and feeling anger. In general, when you hear me talking about anger, I’m talking about the feeling named anger in English.

Anger is a normal feeling with a super power: it gives us the energy to change a situation that we consider to be unsustainable. We can express the feeling of anger verbally by saying for example: “That thing makes me really angry”, “I can’t talk right now, I am very angry about what I just heard”.

Let’s also note that there may be other feelings lying below anger, such as sadness, frustration, grief, fear, etc.

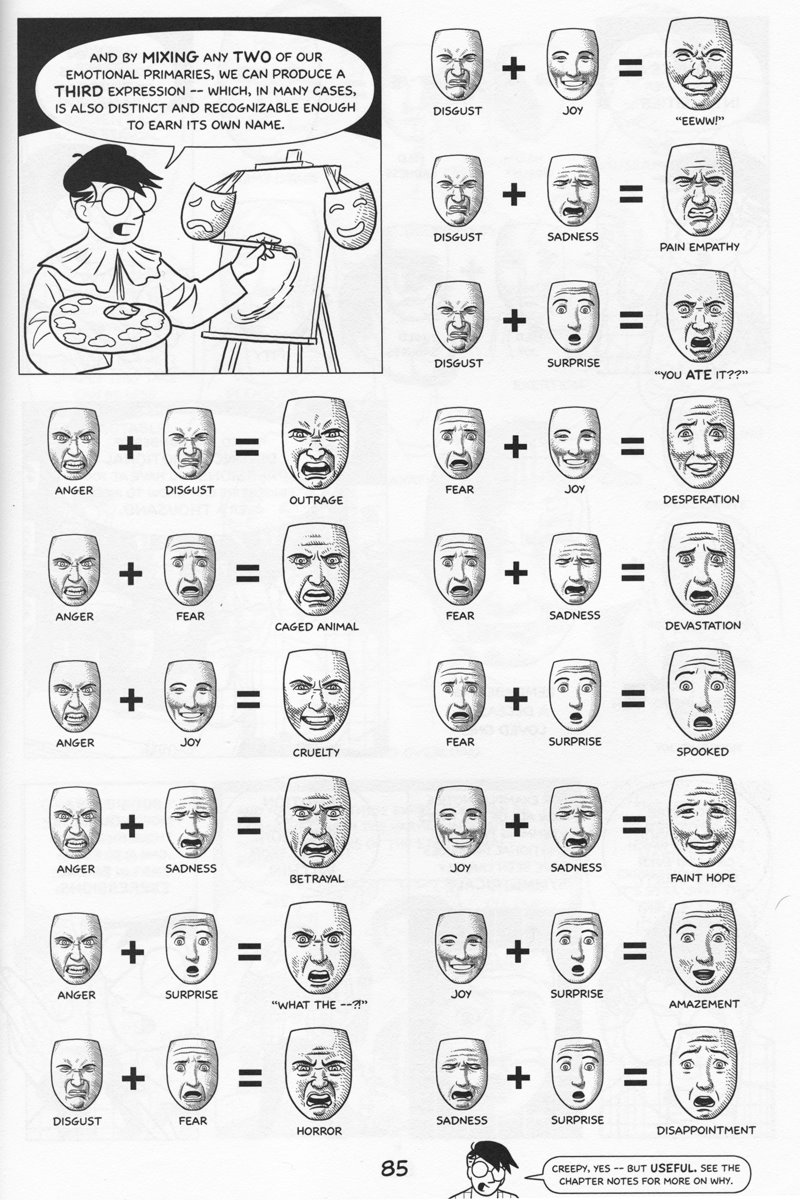

This is a page from the wonderful “Making Comics” by Scott McCloud. (Yes, emotions are complex! See some more of Scott McCloud’s pages about emotion in comics)

Bottling up feelings

Most of the time, people don’t get angry suddenly, even though it might seem like that from the outside. Instead, they’ve been bottling up feelings for a while, and at some point, a small trigger is enough to make the bottle overflow. The reasons for bottling up feelings can be as diverse as people:

- Low self-esteem: not thinking one has the right and the capacity to express unpleasant feelings

- Not knowing how to express unpleasant feelings. For example not having learnt to say: “I am not comfortable, I’ll leave now, I’ll get back to you once I know what’s going on / if this is about me / if I feel like it.”

- Not trusting one’s own feelings, specifically common in people who have been victims of gaslighting

- Repressing emotions, specifically anger, sometimes to the point of not being able to feel one’s own feelings anymore

- Not being able to express disagreement and instead applying the fawn response: trying to please the other in order to avoid further conflict. See: Fight, flight, freeze, or fawn

- Not being able to express boundaries: “stop”, “this is enough”, “I don’t accept this”, etc.

- Not being in a situation or a space in which feelings can be expressed freely, for example a workplace or a hierarchical situation where this might be disadvantageous

These are just some examples I can come up with in 3 minutes, the list is non exhaustive.

When someone’s bottle overflows, their peers can be confused and not know how to react to what they perceive as a sudden outburst — while what they are seeing might just be the other person’s first time tentative of saying “no” or “stop”. Oftentimes, the responsibility for the situation is then put on the shoulders of the person who supposedly “exploded”: they have been behaving differently than usual or not within the expectations, right?

Well, it’s not that simple. Conflicts are relational. The other party might have ignored signs, requests, feelings, and needs of the angry person for a while. Maybe the relationship has been deteriorating since some time? Maybe there was a power imbalance, that has never been revisited, updated, questioned? Or maybe their bottle is being filled by something else in their life and getting too small to contain all the drops of suppressed emotions. People change, and relationships change. We cannot assume that because a person has accepted something for months or years, that they always will. I think that anger can be a sign of such change or need thereof.

A message has four sides… and that creates misunderstandings

Friedemann Schulz von Thun has created a theory, the four-sides model, that establishes four facets of a message:

- Fact: What is the message about?

- Self-disclosure: What does the speaker reveal about herself (with or without intention)?

- Relation: What is the speaker’s relationship towards the receiver of the message?

- Appeal: What does the speaker want to obtain?

Let me adapt Schulz von Thun’s example to a situation that happened to me once: I came to a friend’s house and I smelled some unknown thing when I entered the apartment. I asked: “what’s that smell?” I actually never bake, so I don’t know anything about whatever it is people put into cakes. I wanted to say: I don’t know what that smell is, tell me what it is? She replied: “You never like anything I do, my furniture gets criticized, my cake’s not right, and you criticize me all the time.” We ended up in such a big misunderstanding that I left her house 5 minutes after I arrived.

With Schulz von Thun’s model we can understand what happened here:

The speaker’s question “What’s that smell in the kitchen?” has four sides:

- Factual: There is a smell.

- Self-disclosure: I don’t know what it is.

- Relational: You know what it is.

- Appeal: Tell me what it is!

The receiver can hear the question with 4 different ears:

- Factual part: There is a smell.

- Self-disclosure: I don’t like the smell.

- Relationship: You’re not good at baking cake.

- Appeal: Don’t bake cake anymore.

At this point, the receiver will probably reply: “Bake the cake yourself next time!”

Behind the message

Sometimes, we hear more strongly with one ear than with the other ears. For example, some people hear more on the relational side and they will always hear “You’re not good at …”. Other people hear more on the appeal side and will always try to guess into a message what the other person wants or expects of them. People on the autistic spectrum often hear better with the factual ear, and do not understand the other layers of the message.

Form and contents of a message

Getting back to anger, I think that it’s often not the contents — i.e. the factual facet — of a message that triggers our bottle to overflow, but the (perceived) intention of the speaker, i.e. the appeal facet.

For example, a speaker might have an intention to silence us by using gaslighting, or tone policing. Or a speaker wants to explicitly hurt us because that’s how they learnt to deal with their own feelings of hurt.

The actual relation between speaker and receiver also seems to play a role in how anger can get triggered, when we hear with the relational ear. There are many nonverbal underlying layers to our communication:

- The position of both speaker and receiver to each other: are they equals or is there any kind of power imbalance between them? A power imbalance can be a (perceived) dependency: For example, one person in a friendship has a kid and the other one regularly helps them so that the parent has some time to advance their work or career: this can create a feeling of not being good enough by oneself and having to rely on others. Or there is indeed a dependency in which the speaker is a team lead and the receiver a subordinate.

- The needs of each person: a need to solve problems quickly for one person might conflict with the need to be involved in decision making of the other person. (See Taibi Kahler’s drivers)

- The inner beliefs of each person: in childhood we might have constructed the inner belief: “You’re okay, I’m not okay”, or “Nobody cares about what I want”, or “I have to be nice (friendly, hardworking, strong, etc.) all the time otherwise nobody loves me” - as some examples.

So, suppose person A offers to help person B, and what person B hears instead is their overprotective mother instead of their friend. Person A might be surprised to see B overreact or disappear for a while to get back their feelings of autonomy and integrity as an adult.

Or person C expresses she’d “like to handle problem X like this” while person D might well not hear this as a proposal to handle a problem, but as a decision made without involving her. Which might propel D back to her childhood in which she could also not take decisions autonomously. Then D might react like she would react as a child, slamming a door, shout, run away, freeze, or fawn.

Communication is complex!

So, whenever we hear a message, not only do we hear the message with four ears, but also, we hear it with our position, our needs, and our inner beliefs. And sometimes, our bottle is already full, and then it overflows.

At that point, I find it important that both sides reflect on the situation and stay in contact. Using empathy and compassion, we can try to better understand what’s going on, where we might have hurt the other person, for example, or what was being misunderstood. Did we hear only one side of the message? Do our respective strategies conflict with each other?

If we cannot hear each other anymore or always hear only one side of the message, we can try to do a mediation. Obviously, if at that point one side does not actually want to solve the problem, or thinks it’s not their problem, then there’s not much we can do, and mediation would not help.

The examples above might sound familiar to you. I chose them because I’ve seen them happen around me often, and I understand them as shared patterns. While all beings on this planets are unique, we share a common humanity, for example through such patterns and common experiences.

05-02-2021